I wrote Marathi article few years ago on my mostly non-professional experiences. However, some of my non-Marathi family members and friends requested this article to be translated in English. So, here you go!

As we get old, we all tend to dive into our fading brain cells and pull out some old memories. Then we ruminate on those memorable experiences in boring meetings, on the toilet bowl, when we go to bed or when we are pretending to listen to our spouses. In my case, I even wrote some nostalgic articles in Marathi on some of these unique memories, such as my excursions as a foodie. But what I have never done is to take a comprehensive stock of all my experiences. Now, my schoolmates have requested me to write this entire autobiographical journey. For some of you, it could be an interesting read, and for others, it could be just a diatribe.

To ensure that you are not bored with long articles in this fast-paced world, I will write the experiences in non-chronological bullets and then, I will let you imagine interesting stories behind these bullets. For example, when I write that “In my 9th grade, five of us walked from Dombivali (my hometown in India) to Raigad (Fort capital of the founder of the Maratha Empire, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj)”, I will let you envision the stories yourselves behind such an 8-day-walk. These stories could include burning pain of bulging blisters all over our feet, anxious palpitation of young hearts knocking on random strangers’ doors in the dark for overnight shelter, and taste of terribly cooked scorched rice next to the fast-paced thoroughfare under the hot sun.

Oh yes, we did not share our (Anjali’s and mine) personal anguishes in this write up. Let them remain tucked away in our hearts.

OK, shall we start?

I used to spend evenings in fifth and sixth grades catching fish in the sewer nullah flowing next to our home. Yes, that is really, really true! My hometown fruit market used to be occasionally flooded in monsoon rain and rotten oranges used to flow in the rapids of this nullah. I would lie flat on the stomach on the sewer bridge in the soaking rain and would try to catch these swaying oranges rushing through the overflowing rapids of the nullah. Believe me, it was the ultimate, adrenaline rushing fun game ever existed in the whole world. Once my teacher had pulled me out of the sewer and reprimanded me in front of the girls from my school. Very very embarrassing moment indeed! (Of course, not so much because teacher caught me but because girls were laughing at me.)

As I mentioned earlier, we went on an 8-day walking trip to Raigad from Dombivali. The team of fabulous five included “matured(?)” adults with ages ranging from 10 to 14. We had no idea of where we would stay overnight and what we would eat. Parents said “yes” and there we went! Totally crazy endeavour! In the evening, we would literally knock on any random home in tiny villages and request them to accommodate us for the night! What a hospitality that we received from all these impoverished families! With such experiences, it was so easy to develop unwavering faith in humanity! Just unbelievable experiences!

I loved to swear in Marathi in my school. Later in college (IIT, Bombay), I added fancy English “vocabulary” to improve my “sophistication” of swearing. In my literary exuberance of cursings, if some gentleman gets red-faced and unsettled, I used to refer him to one of the popular Marathi theater drama “Tee Phulraani” (based on George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion) by the most respected Marathi author Pu. La. Deshpande. The Professor in this play also used to swear and say that “Such beautiful filthy words are adorned jewellery of any self-respecting language.” I even earned second place in the dorm competition in cursing! But, of course, I have never sweared in front of younger children and elderly people.

In my final year in high scool, some of my friends incited me to take math AP class. Our principal was reluctant to conduct AP classes. But somehow, the motivated leaders of our pack persuaded the principal. Further, my close friend Arun Joshi, provoked me to take Arithmetics AP class at the same time. Unfortunately, we had to learn it ourselves, as our principal did not want to offer such a class only to three crazy students. Here in USA, students may not understand all the fuss of taking AP classes. But this entire self-learning episode during the most crucial academic year was on the borderline of irrational stupidity.

I had a fantastic relationship with my in-laws. I could carry long conversations with Anjali’s mom. (How many people do you know, who have such long conversations with their mothers-in-law?) Both in-laws have now passed away. But we had a nostalgic quiet revival of those memories in Anjali’s nephew’s pre-pandemic wedding. That was a great detour to the past!

Until now, I have travelled to 52 countries, sometimes for work and sometimes for pleasure. Now-a-days, our family has unusual modus operandi for such trips. Eat unique local food, sit around watching people go by on the street and observe their daily life, visit local markets and roam around in nature. We do not chase those conventional sight-seeing places anymore that would be promptly forgotten in no time! Some of the journeys are etched in our brain. Galapagos, Amazon Jungle and Tanzania were simply mind-blowing places. And how can I forget our visit to my brother in New Zealand followed by a family trip with my parents? That was the last trip with my ever-enthusiastic mom!

I have done trekking for more than 300 days in the Himalayas. On the Kalabaland expedition in 1982, at the northwest tip of the China, Nepal and India border, we had to stay above the snow line for 40-45 days, where snow never melts throughout the year. The only way to get water above the snow line was to melt the snow. We were short of money, short of sufficient porters and short of fuel. Obviously, water was rationed only for drinking and cooking purposes. What does that mean? It means brushing and taking showers were completely skipped for the entire 45 days! Woohoo, perfect siuation for a lazy bum like me! Never mind that based on my current appearance, many friends think that I do not take showers even today. Hahaha!

When I was working in the Tata AutoComp Systems (TACO) in Pune, I led the negotiations for four joint ventures (JVs). Later, I had an opportunity to nurture these JVs as a board member on behalf of the Tata group as well. Considering that the Tata group had 200 companies, very few select strategic companies were led by Mr Ratan Tata. We were one of those lucky companies. We used to meet him once every three months in the board meeting of TACO. I even had an opportunity to have two-on-one lunch with him along with my boss. I learnt a lot from this unbelievable Guru and could run the business unit without any corruption.

When Aarti and Tejas were 4 and 6-year-old tiny children, we literally sent them alone to Sydney to my brother’s home (Yup, this mega stupidity is true!). Kids even changed the flight in Singapore with the help from the flight attendant. Later, our bravado melted away. Shit-scared with the prospects of these kids coming back alone, I promptly went to Sydney to bring them back myself. Kids developed such a strong bond with my brother and sister-in-law that while returning, except me, the entire Anturkar family was crying. That bond is still very very strong. My niece’s wedding was a similar amazing bonding experience in our lives.

I met an elected government official in 1998 near Pune for getting approval of one industrial set up. He requested 60 million Rupees as a bribe (approx. 1 million USD), 30 million Rupees for himself and 30 million for one political party in power. Unfortunately for him, I was brought up by my strong-valued parents and led by Mr Tata. I told him to go to hell. We set up the facility in Hinjewadi, a small village near Pune at that time, where the Tata group had already set up the industrial infrastructure. Government did eventually establish today’s well-known software park here and credited the Tata group for all the initial work. Yahh, you can show a finger to the corruption and still built great industrial businesses in India.

I really really love to explore all kinds of food. I have enjoyed some crazy exotic dishes, such as grasshopper powder (Chapulines), horse and crocodile meat, yucky home-made beer in Kerala, Yak butter tea in Ladakh and eggs of the large ants (Escamoles). After all that exotic food, my number one favourite dish is still home-made traditional Marathi desert called Basundi (based on thickened milk).

This next experience is a little difficult for you to imagine! In the Kalabaland expedition, at one point, my team member Nitin Dhond and myself were the only two members present in one of the camps. Suddenly, snowfall started with a blinding whiteout. Intermittently, one of us had to go out to remove snow from this tiny tent to avoid its collapse. However, the most important challenge was that we had no idea how long this snowstorm would last. Rationing food and fuel (for water) in that cold weather was one of the most stressful and anxious moment in my life!

Incidentally, in that expedition, our team scaled seven peaks, including three peaks that were previously never ascended. Did you know that the International Mountaineering Federation let the climbers designate the names for such virgin peaks that are recognized in all official maps? Our team did name the peaks using the local tradition, language and norms. This was a very proud moment.

At the age of sixty, I had an intense, sudden heart attack with 100% blockage of the main artery (Left Anterior Descending artery called LAD) going to the heart. Apparently, such heart attack with 100% blockage of LAD is called a “widowmaker” heart attack due to patient’s extremely low survival rate. Lord Yama (the Indian God of death) was knocking on the door. But the door never opened. With blessings from my parents, I was neither in pain nor had any worries. I exercise a lot. Why me? I have no blockage due to the plaque build-up. Why me? I do not smoke or drink. Why me? Why me? Surprisingly, none of such “why”s popped up in my mind. I had a blast with nurses and doctors for five days in the ICU. Oh well, who says that we should only have experiences of our choice? Lol.

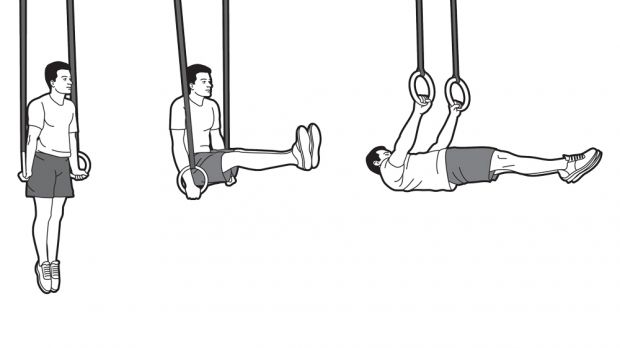

I was in the Gymnastics team in college. Our coach, Mr Khatri, was from the army and did not hesitate to smack 20-year-old adult students with his shoes. “Learn to enjoy the pain” was his ruthless mantra.

Before I entered the crucial final year in the high school, I scored a pathetic 46/100 in the English language exam. When teacher visits you at home, you know that you are in deep, deep trouble. Our teacher, Ms Chemburkar, came home and told my parents that “your child is in trouble!” In India, knowing English language was (and is) the gateway to higher education and rosy pastures throughout the life. After the visit from my teacher, my uneducated parents told me something that I will never forget. “You are a responsible student, kiddo! NOBODY else can help you in shaping your future, nobody can!”, the unforgettable ultimate lesson called empowerment! They did introduce me to one Professor named Mr Gadgil, who used to teach English in the SIES college. He started reviewing one essay every day from me for the next 300 days and told me to start “thinking” in English. Even then, after so many years, I feel that my English is sketchy! Oh well!

Emergency declared in India by Ms Indira Gandhi in 1975 was a scary time in my hometown. Many political opponents were jailed. Many families lost their daily income and were devastated. For whatever reason, Ms Gandhi lifted the emergency and declared the elections in 1977. Many intellectuals and writers started campaigning against her autocracy. Some of my friends and I started raising donations in various political gatherings in this oppressive environment without worrying about potential repurcussions. I was later appointed as a polling agent in Mumbra (a small town near my hometown). I was not even an adult and had never seen the election center from inside. This town was perceived to be pro-Gandhi. I was scared. I had no idea what to expect. Voters would come in, stare at me and would quietly proceed to vote. In the afternoon, one old lady showed up. I was scared when she started walking towards me. Can you believe that she handed over to me a small wildflower? What a sigh of relief! With that kind of compassion from the ordinary people, seemingly invincible Ms Gandhi was thrown out of power. I eventually campaigned only once more in 2020 in the USA. I hope that I never have to campaign in my life again!

My father had a weird ailment that he acquired while swimming in some lake in his twenties. Raw, painless flesh would grow on his upper lip, in his throat and in the nasal cavity. As this unsightly red flesh grew, it used to block his breathing tract. My father required a surgery every six months in the government hospital to physically remove this heidious outgrowth. After surgery, until he recuperated, the blood needed to be sucked out of his throat using a vacuum every ten minutes while he was still under the influence of anesthesia. As a small child, I have spent many nights removing the blood. It is a very long story, but one fine morning, some doctor at the Haffkine Institute developed a vaccine for his specific problem, and boom, the problem vanished after unbelievable turmoil of 25 surgeries. Can you believe that even in crowded local trains in Mumbai suburbs, nobody, I mean nobody, would even try to come closer to my dad due to his terrible look?

My father was a blue-collar worker and mother was a primary school teacher. None of them went to college and barely finished school. Income was limited. And then there used to be frequent labor strikes in my father’s manufacturing unit. How would my parents then provide two meals on the table every day? Well, he used to buy in bulk and sell in retail the vegetable oil and tea powder in the neighborhood (probably because these commodities had higher profit margins?). Sometimes, I used to help him out. In my academic life, I did learn some fancy math tools, such as Laplace Transform, Eigenvalues and blah and blah. But survival skills that I learnt from selling basic commodities door to door are simply incomparable to the utility of academic sophistication.

My “less-than-ordinary” parents did some extraordinary work. They established a school in Dombivali (my hometown) that exemplified academic excellence. From my seventh grade until I went to college, the only two rooms in our home used to be chock-a-block filled with zillion students from 8am to 7 pm. The only available space for three kids of these dedicated parents and the grandma was in the 70 sq ft kitchen in this “spacious” 535 sq ft. palace. Naturally, most of my student life was spent on the rooftop of our apartment building. That is where I memorized some amazing patriotic poems, read some “juvenile(!)” books, taught math to my brothers and studied really really hard for my high school final exam. Did I tell you that despite a struggle to provide for us, my parents never took one dime of rent from this school that he and my mom established. That is what “walk-the-talk” role models look like!

I did a beautiful and risky Chaddar trek in the Himalayan Ladakh about 8 years ago, involving walking on the frozen Zanskar river for 10-12 days. It was an absolutely mind-blowing experience with some very tricky challenges. On one occasion, we had to walk through waist-deep torrential Himalayan River for 8-9 minutes. To add to the fun, there was ice at the bottom of the river and a lurking danger of frostbite! We walked sideways holding each other’s hands and screaming “ठंडे ठंडे पानी में” (A well-known Hindi song on cold water showers) while simultaneously praying in desperation in our mind! I was also stuck once in the ice boulders. I could see and hear intimidating rapids deep down in the riverbed. Finally, three people somehow pulled me out while lying flat on the ice to prevent triggering cracks with their body weight. After the trek, it took one entire month to bring back any sensation in my legs. I also had to use a donut shaped medical tire for one whole year to fix my tailbone.

With limited means in my upringing, I could never travel away from home. Finally, me and my friend, Arun cajoled our parents to give us some money to travel to North India for 90 days. Most of the time, we found refuge literally on the railway platforms among other homeless people. Eventually we made friends with some of them, who taught us how to take showers under leaking water pipes between two rail lines. We walked and walked across the cities and ate delicious and cheap street food. We did langar (a service) at the spectacular Sikh Golden Temple in Amritsar and offered chaddar (a traditional muslim practice in India) at the well-known mosque at Ajmer.

Two most memorable days in our lives were when Tejas got admission to the University of Chicago and Aarti was admitted to MIT. It was their hard work, their disciplined efforts and their excellence. But we showed off among our friends as if we ourselves went to these great universities. These kids have blown away our minds in their “out-of-the-box” thinking.

I was a culturally starved moron until I finished college. I never saw a play, never went for a concert, never attended a musical opera and never heard any great orators. It is true that my family did not have any disposable income. But I did not even attend free programs. I personally was involved in organizing Bharatratna Pandit Bhimsen Joshi concert (The finest exponent of North Indian classical music) in my college. But I skipped this program completely. Now, I listen to Sanjiv Abhaynkar and Kaushiki Chakraborty, I watch great Marathi plays and visit art museums with my daughter. That is when I realize how stupid (and moron) I was!

I met some stupefying teachers, gurus and friends in my life. Some pursued their life-long passion for mountaineering, some played professional bridge, brilliant ex-defence minister Parrikar exemplified Mr Clean image in Indian politics, Vasant Limaye became a prolific writer and Raju Bhat became a naturalist farmer. Some are at the forefront of research in Math, some wrote books that created the entire new subjects, and many are celebrity business leaders across the world. I recently found out that one of my teachers was the first disciple of Kishoritai Amonkar (the classical musician, referred to as the Goddess Saraswati herself across India). All these down-to-earth, stunning people are working hard to change the world and have made my life colorful. I sincerely can not thank them enough.

There is absolutely nothing common between me and Anjali. In fact, we are at the diametrically opposite end of virtually every aspect of our likings. I love dense curry; she loves watery curry. She wants cilantro in various recipes, I do not. She eats less and I eat more. She loves to spend money and I do not. I can probably list 500-700 such items. But when it comes to our values and our unflinching commitment to build lasting friendships, we have exactly identical thoughts and actions. No wonder, my parents gave her the power of attorney of whatever meagre assets they had. What can I say? I would love to have her as my wife for the next zillion reincarnations.

Bruhan Maharashtra Mandal is the umbrella organization of all Marathi people in the USA. Few years ago, their biennial convention was organized in Michigan under Anjali’s leadership. I participated in the convention, volunteering for “anything and everything”. For those who are not involved in organizing such community conventions, it is really very very difficult to understand the complexities of organizing myriads of concerts, performing multiple theater shows, offering amazing food and arranging accommodation for 4,000 participants in all age groups within the span of four days. I can probably narrate 500 heart-warming stories from this convention. Getting to spend two whole days with my friend and ex-defence minister of India, Shri Parrikar, was one such totally unforgettable experience!

The zing of starting my own company intoxicated me, just like for any other aspiring entrepreneur. I completely failed in this aspiration. I thought that I was bringing unique skills and tools to the plastics components industry to the newly emerging modern auto designs in India. Well, the mighty Tata group and few other well-established western companies were also bringing superior technologies backed by strong finances. I just could not compete. Eventually, the Tata group approached me and asked, “Why do you want to get involved in this messy business of entrepreneurship? Why don’t you join us?” My intoxication had subsided. I readily joined the Tata group. I think nobody teaches how to deal with failures. It was a tough, humbling and still incredible learning experience for me.

Another of my complete failures was to train myself for the Ironman, the competition involving 4-km swimming in open water, 180-km cycling and 42-km marathon, all to be finished in 17 hours. I lost cartilage in my right knee at the beginning of the training itself. Entire knee was then replaced with the metal knee in one of the most abusive and painful surgeries and rehabilitation.

Another of my crazy aspirations that Anjali tolerated was to return to India after spending 10 years in the USA. We felt that we owe it to my motherland that provided us with top-notch, world-class and ridiculously cheap education ($12 per year tuition fees). But it was Anjali who worked hard for my esoteric passion, settling in India for 11 years and then returning to the USA. Do you know that Anjali travelled and worked in Detroit for every 15 days a month for long five years to provide means for the family? (I suspect that she can write more exciting stories of her life than me!) I become teary eyed just thinking about her efforts at that time!

On behalf of Dandekar Economics Institute, I was appointed at my tender age of 15 to overview the government’s Employment Assurance Scheme in a very very remote, undeveloped region in Wada (in Thane district). Imagine the visual of a mother feeding tree leaves to her small baby to quell baby’s hunger? Imagine its impact on my formative age? No philosophy, no preaching, no creative mindsets, no religious comfort of faith, nothing, nothing at all can replace the desperation called hunger! I am speechless even right now, just remembering that scarred visual.

I worked at General Motors in purchasing for 15 years. Almost always, the suppliers wanted higher profits and we wanted cheaper, high-quality components. I initiated two awesome three-year projects for GM. These complex projects involved zillion teams, required delicate communications and were very risky. I could write 800-page books on each of the projects, probably in my next reincarnation after the expiration of all confidentiality clauses with GM.

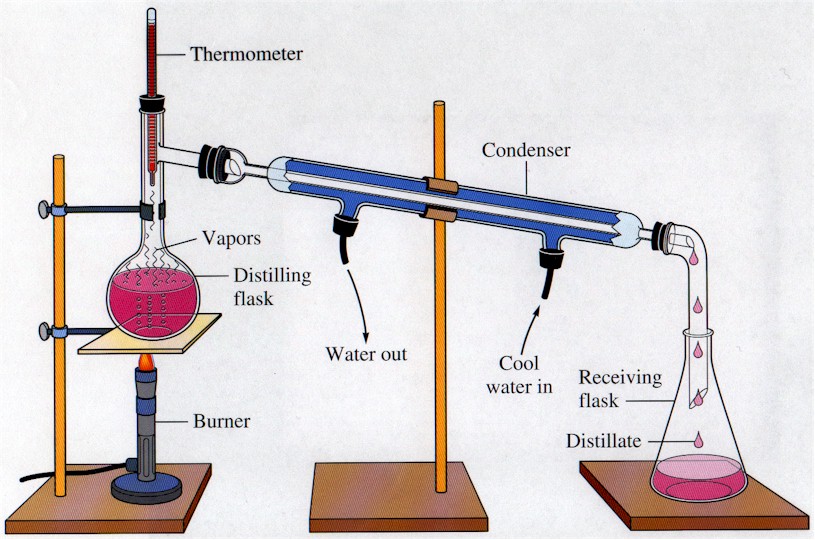

A stationary bike falls down instantaneously and a rolling bike travels hundreds of miles. Many natural phenomena, such as black holes, ocean waves and thunderstorms can be explained by the identical mathematical principles. Using the same concepts, I developed a model that could predict multilayer plastic flow and increase quality and production of some plastics products. I got my PhD primarily because of some brilliant work by people in last 100 years. Isn’t it easy to stand tall on others’ shoulders and then I get to “show-off” my PhD?

For all my five years in college, I neither shaved nor trimmed my beard. Most of my friends still call me “Dadhi” (which means beard in most north Indian languages)

We organized a high-altitude trek called Himankan for 200 students. A long beard, crew-cut hair, khaki woolen gown and a pair of flip-flops of two different colors was my attire throughout this program. My daily responsibility was to buy groceries from local shops in a nearby town called Manali. Once, a fellow trekker got down from the bus while I was walking on the main street. He looked at my attire and said, “Dadhi, are you wearing anything inside your gown at all?” I said “no.” He could not believe it and challenged me to prove it. I did prove to him then and there that I do not lie. This trekker was so shocked, that he did traditional Indian salutation of respect where he laid flat on his tummy on my feet right in the middle of this busy road.

I have completed 62 years of my life and my bucket list keeps growing. First thing first! I need to complete the stupendous 2,200-mile long Appalachian Trail spanning 14 states and involving one million feet climbing up and down. I need to learn Spanish and Sanskrit, want to visit north and south poles, do cycling on salt lakes in Bolivia and India, explore scuba diving in Galapagos after learning swimming, complete pilgrimage to the Vitthal temple in Maharashtra, learn history of paintings, see world field hockey championship and so on. Then there are dolomites, great walks of New Zealand and many many treks in the Himalayas. The ride has just begun!!!!!